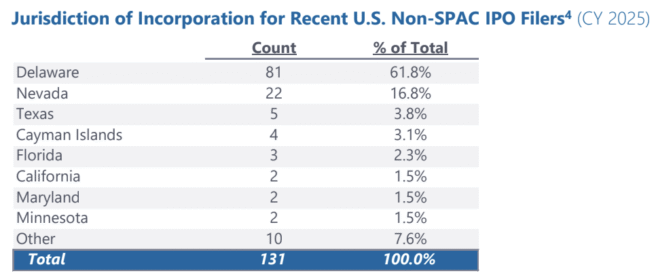

Following up on January’s post on this topic, we have some updates. This is the list I’ve compiled so far.

Announced Moves as of February 26

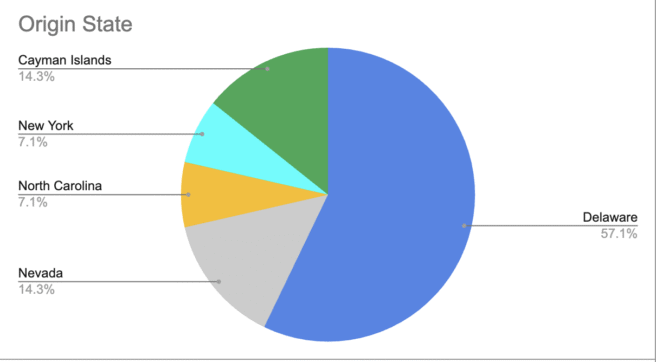

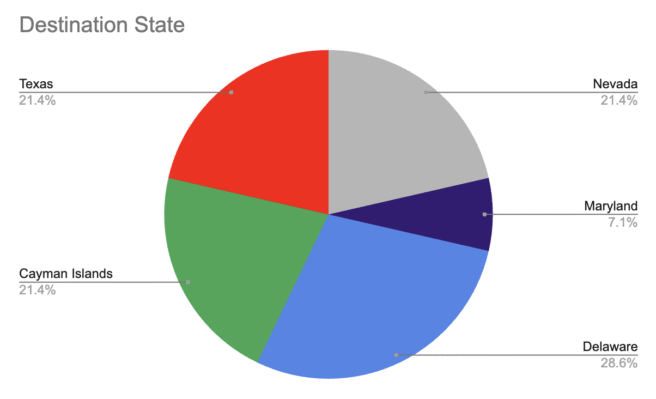

| Company Name | Stock Ticker | Origination State | Destination State |

| TruGolf | TRUG | Delaware | Nevada |

| Forian, Inc. | FORA | Delaware | Maryland |

| LQR House | YHC | Nevada | Delaware |

| CBAK Energy | CBAT | Nevada | Cayman Islands |

| Cheetah Net | CTNT | North Carolina | Delaware |

| Galecto | GLTO | Delaware | Cayman Islands |

| Resolute Holdings Management, Inc. | RHLD | Delaware | Nevada |

| Forward Industries, INC | FWDI | New York | Texas |

| EQV Ventures Acquisition | FTW | Cayman Islands | Delaware |

| Datadog, Inc. | DDOG | Delaware | Nevada |

| Haymaker Acquisition Corp 4 | HYAC | Cayman Islands | Delaware |

| CDT Equity | CDT | Delaware | Cayman Islands |

| eXp World Holdings | EXPI | Delaware | Texas |

| ArcBest Corp | ARCB | Delaware | Texas |

We’ve got an additional seven entries since the last update with some multi-billion dollar companies announcing for Texas now, including ArcBest which came out today.

To make this easier to understand, I’ve recruited a couple of Research Assistants to help with data visualizations, so many thanks to Ethan Viator and Hunter Hawkins for helping pull these together. You can see my full data here with some notes for follow up from our two brave research assistants. I’ve also added a column to track disclosed outside counsel. We’re just looking to capture firms that have provided advice and are identified that way in the proxy statements. Our hope is that collecting this information will make it easier to then go and look at other things later. For example, I want to see whether the market reacts to these announcements.

Turning to the visuals, the first two show where companies are leaving and where they are going. Nevada, as the Silver State, obviously gets the silver coloration.

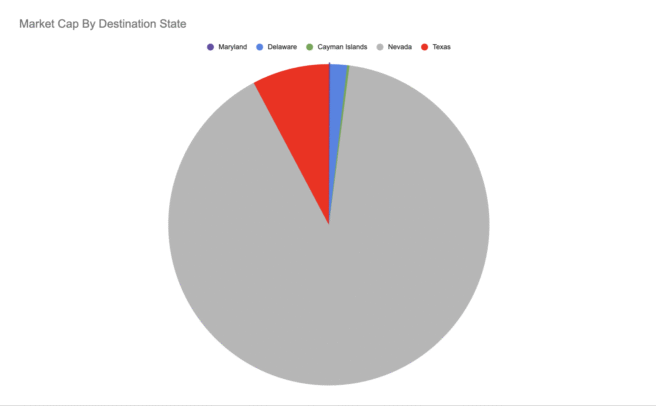

We also put together a basic pie chart to show market cap by jurisdiction. The big driver for Nevada’s market cap position is Datadog with its roughly $44 billion market cap.

I wanted to get this out in advance of tomorrow’s symposium at SMU. It’s titled Welcome to Ya’ll Street and should have some interesting discussion. These recent moves should inform the panels about what to expect.

In terms of what the year may hold, I know that “proxy season” usually runs from about April to June for peak activity. We’re at fourteen moves before the end of February at this point–and Delaware is the most popular destination at this moment. I still think we’ll see an uptick from last year, but I don’t know how significant it will be.

Quick Thoughts on ArcBest

The proxy just came out today, so I haven’t been able to spend as much time reading it as it deserves, but ArcBest‘s move seems different than others. Notably, it does not seek maximal protection available under Texas law:

In furtherance of the Board’s intent to preserve stockholders’ existing rights, the Texas Charter includes provisions that expressly opt out of Section 21.373 (regarding ownership and solicitation thresholds to submit shareholder proposals) and Section 21.552(3) (regarding ownership thresholds to bring derivative lawsuits) of the TBOC. As a result, the Company will not be subject to, and cannot elect to be subject to, these provisions without an amendment to the Texas Charter, which would require separate shareholder approval. The Board believes that Sections 21.373 and 21.552(3) not only significantly depart from shareholder rights under Delaware law, but also are inconsistent with shareholder value and preferences.

In terms of reasons for the shift, ArcLight expressed concern about Delaware’s litigation environment and a desire to have a closer connection to the incorporation jurisdiction. This is how it put it:

The Board believes that a closer geographic nexus between its operations and its state of incorporation would benefit the Company and its stockholders because, among other things, it reduces the costs to the Company for directors and officers to attend legal proceedings related to the Company, and it increases the possibility that politicians and judges making decisions about the Company have a better understanding of the effect of such decisions on the Company and its long-term value.