Hennion and Walsh, a FINRA member firm, has taken an unusually aggressive position, claiming that because it has procured expungements through the FINRA forum, members of the public cannot discuss the underlying conduct. A cease and desist letter sent to a law firm claims that the firm “posts information relating to Hennion and Walsh, Inc. and its’ [sic] employees which has been found to be false and has been ordered to be expunged.” The letter goes on to claim, without authority, that it’s “illegal to provide a false statement . . .of an individual’s character and/or reputation” and that unspecified “relevant records reflect the information you have posted for public consumption has been deemed to be false, was ordered to be expunged and that order has been confirmed in a court of competent jurisdiction.”

The letter doesn’t specify exactly what statements it wants removed, but I presume it’s blog posts or other things featuring news of past Hennion and Walsh settlements or complaints against Hennion and Walsh employees. These are all fairly typical things for a plaintiff-side firm to post. If one investor has filed or settled a claim against a particular broker, there may be other aggrieved investors out there looking for counsel. Having a blog post up informs the public that the attorney watches the space and would probably welcome a call for help.

So, this brings me to the key question, does the fact that expungements have been procured through the FINRA arbitration forum mean that law firms must send all those old posts down the memory hole? The reality here is that the best available research here from Colleen Honigsburg and Matthew Jacob shows that brokers who have obtained expungements are actually more likely to attract future customer complaints than similarly situated brokers who do not obtain expungements. Brokers with expungements are “3.3 times as likely to engage in new misconduct as the average broker.”

For many years, the process for expunging information about stockbrokers has been fundamentally broken. I’ve written about the enormous problems with the expungement system and called for a shift to a more regulatory framework. FINRA has also moved and significantly reformed its expungement process with new rules going into effect in 2023. Yet the prior system’s problems don’t go away immediately. One broker recently secured a record number of expungements under the old rules in an award that came out in September this year.

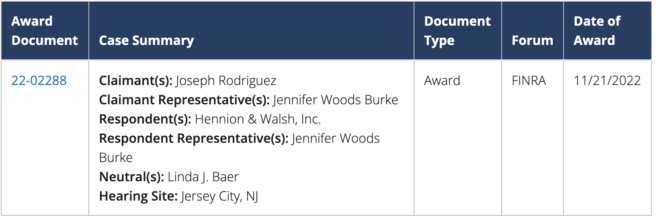

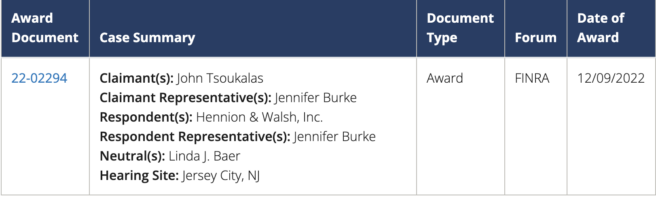

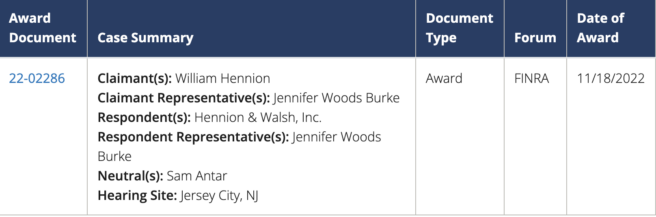

Some Hennion and Walsh expungements seem to exemplify the problems under the old system. Consider four different expungements secured by Hennion and Walsh brokers. In each of these matters, the broker seeking expungement filed a claim against Hennion and Walsh. Both the broker and Hennion and Walsh were simultaneously represented by Hennion and Walsh’s in-house counsel, Jennifer Woods Burke. All of these cases employed the ethically dubious dollar-trick strategy.

These cases raise two red flags for me. The dollar-trick strategy in this circumstance seems particularly hard to defend. It also strikes me as a violation of the concurrent conflict of interest rules.

Did The Damages Claims Have Any Basis?

Let’s start with the dollar-trick issue. I call the strategy ethically dubious because under ABA Model Rule 3.1 lawyers are only supposed to assert claims if they have a “basis in law and fact for doing so that is not frivolous, which includes a good faith argument for an extension, modification or reversal of existing law.” Asserting a $1 damages claim for the purpose of securing a single arbitrator allowed claimants to avoid the three arbitrators the FINRA Rules called for claims for non-monetary relief. Wanting non-monetary relief without wanting to pay fees for non-monetary relief doesn’t strike me as a claim that has some basis in law and fact. In an expungement hearing, I once asked a broker who had filed one of these claims why he thought his firm owed him a dollar. He was baffled and had no idea.

Here, the lawyer represented the broker and the firm in the same matter. Surely the lawyer would be well-positioned here to know whether there was any basis for seeking monetary damages. That the claim was dismissed at the hearing–as all other dollar-trick claims were–makes it appear as though there was no basis for the damages claim than a desire to avoid paying fees.

Simultaneous Claimant and Respondent Representation

The other major ethical issue with these expungements is the concurrent client conflict of interest. Burke represented both the claimant and the brokerage in each of these four matters. That raises an issue under Model Rule 1.7. The ethics rule states that you have a concurrent conflict if “the representation of one client will be directly adverse to another client.” It goes on to provide that you can only waive the conflict if “the representation does not involve the assertion of a claim by one client against another client represented by the lawyer in the same litigation or other proceeding before a tribunal.” Here, Burke simultaneously represented both the claimant and the respondent in the same proceeding before an arbitration tribunal.

Comment 17 to the Rule explains:

[17] Paragraph (b)(3) describes conflicts that are nonconsentable because of the institutional interest in vigorous development of each client’s position when the clients are aligned directly against each other in the same litigation or other proceeding before a tribunal. Whether clients are aligned directly against each other within the meaning of this paragraph requires examination of the context of the proceeding. Although this paragraph does not preclude a lawyer’s multiple representation of adverse parties to a mediation (because mediation is not a proceeding before a “tribunal” under Rule 1.0(m)), such representation may be precluded by paragraph (b)(1).

With Burke representing both the brokers and the firm in the same proceeding, you cannot pretend that the “institutional interest in vigorous development of each client’s position” was achieved. You also cannot pretend that the public’s interest in preserving public information about past complaints against brokers was vigorously represented.

For a long time, FINRA expungements were often sham proceedings. In most expungement cases, no person with any interest in surfacing information militating against expungement ever spoke to the arbitrator. FINRA has put in place rule changes to deal with the problem and now allows state regulators to appear in these proceedings on the theory that they may serve as better defenders of the public’s interest in information.

Ultimately, Hennion and Walsh secured its expungements through this dubious process, for whatever that’s worth. But they should not be able to use expungements secured through this dubious process to force everyone else to pretend that no complaints were ever raised about their personnel in the past. They had past complaints. They got them expunged. The process they used seems ethically dubious. They won four expungements when the same lawyer represented the claimant and the firm before an arbitration tribunal. Take the facts for what they’re worth.