No one needs a recap of where we were on Elon Musk’s 2018 pay package, but just in case: in 2024, Chancellor McCormick concluded after a trial that Elon Musk was a controlling shareholder of Tesla, and that the pay package was a conflicted transaction that was not entirely fair to the stockholders. In particular, she found that Musk himself controlled the process by which the compensation committee set his pay, and largely made up his own contract with the comp committee serving as a rubber stamp. As a remedy, she ordered that the pay package be rescinded.

Today, the Delaware Supreme Court did not question any of Chancellor McCormick’s actual findings regarding how Musk’s 2018 pay package was negotiated, the control and interference that Musk exercised over the process, or even the unfairness of the award itself. Instead, the sole basis for the holding is a kind of Rumpelstiltskin argument: the plaintiffs used the word “rescission” when requesting a remedy, but this case does not meet the technical requirements for rescission – because rescission requires that both parties be restored to the status quo ante, and there’s no way to give Musk back his years working for Tesla after 2018. “It is undisputed,” said the Court, “that Musk fully performed under the 2018 Grant, and Tesla and its stockholders were rewarded for his work.”

(It was disputed, actually. Per Chancellor McCormick, “Defendants failed to prove that Musk’s less-than-full time efforts for Tesla were solely or directly responsible for Tesla’s recent growth, or that the Grant was solely or directly responsible for Musk’s efforts.” Details.)

Nor could the appreciation in value of his preexisting equity stake serve as a substitute to restore the status quo, because, per the Court, “[t]he benefits from his preexisting equity stake were not the compensation he was promised if he achieved the 2018 Grant milestones.” Which is an argument that proceeds on the assumption that Tesla’s “promise” was a fair one achieved at arm’s length, rather than one manipulated by Musk himself – which is … not what Chancellor McCormick found.

Okay, so the plaintiffs can’t technically receive rescission, because both parties can’t be restored to their 2018 positions. What about remedies like disgorgement or rescissory damages, then, would they be appropriate? A ha! Plaintiffs used the word “rescission,” not “rescissory damages” and not “disgorgement,” so the Court need not ponder such unlikely hypotheticals.

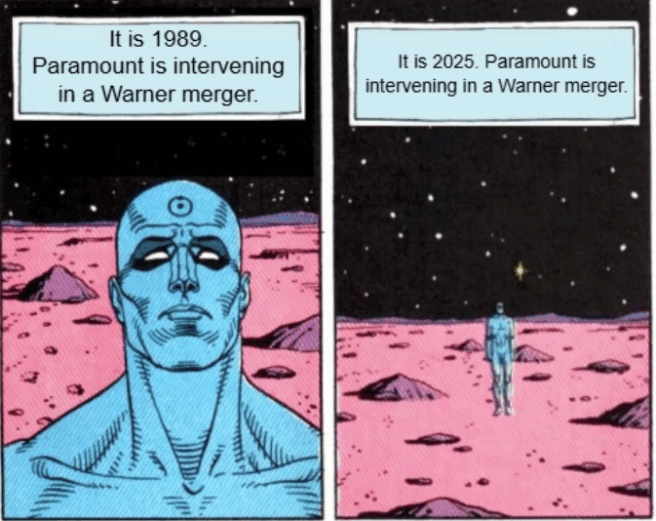

Which is to say, in the grand tradition of Paramount v. Time, widely viewed as a response to Martin Lipton’s Interco memo, the opinion reeks of political expediency (an impression buttressed by the fact that it was issued per curiam – no individual judge wanted to be associated). The Court took a hot potato and found a way to toss it without saying anything at all.

But one difference between Tornetta and the Paramount v. Time decision is that in Paramount, the Court found a way to protect the interests of corporate stakeholders from a rapacious form of shareholder wealth maximization. In Tornetta it … did the other thing.

And … a Very Special Shareholder Primacy podcast! Me and Mike Levin close out the year with a crossover episode with our sister pod, Proxy Countdown, featuring Matt Moscardi and Damion Rallis of Free Float LLC. Here on Spotify, here on Apple, and here on YouTube.